The Victorian Era: History, Society, and Literary Culture

Chartism

With the Great Reform Act 1832, voting rights were given to the property-owning middle classes in Britain. However, many working men were disappointed that they could not vote.

Chartism was a working class movement which emerged in 1836 in London. It expanded rapidly across the country and was most active between 1838 and 1848. The aim of the Chartists was to gain political rights and influence for the working classes. Their demands were widely publicized through their meetings and pamphlets. The movement got its name from the People’s Charter which listed its six main aims:

- a vote for all men (over 21)

- secret ballot

- no property qualification to become an MP

- payment for MPs

- electoral districts of equal size

- annual elections for Parliament

Why did the Chartists make these demands?

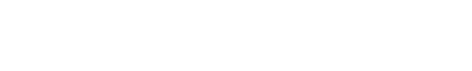

The Chartists presented three petitions to Parliament to make their six point charter law in 1839, 1842 and 1848. Each petition was rejected. The final Chartist petition of 1848, it was claimed, had six million signatures. The Chartists planned to deliver it to Parliament after a peaceful mass rally on Kennington Common in London. According to the Illustrated London News on 15th April 1848, “One hundred and fifty thousand special constables, watchful for the preservation of order, have grasped their useless truncheons and have paraded the streets without meeting a foe.” 15,000 Chartists were said to have turned up. The demonstration was considered a failure and the rejection of this last petition marked the real decline of Chartism. The petition itself was ridiculed and said to contain 1,975,496 names and many forgeries, including the signatures of Queen Victoria and Mr. Punch. Chartist conventions continued until the 1850s but without mass support.

Opponents of the movement feared that Chartists were not just interested in changing the way Parliament was elected, but really wanted a revolution. They also thought that the Chartists, who said they disapproved of violent protest, were in fact stirring up a wave of riots around the country. On 4 November 1839, 5,000 men marched into Newport, in Monmouthshire, and attempted to take control of the town. Led by three well-known Chartists: John Frost, William Jones and Zephaniah Williams, they gathered outside the Westgate Hotel, where the local authorities were temporarily holding a number of potential troublemakers. Troops protecting the hotel opened fire, killing at least 22 people, and brought the uprising to an abrupt end.

Support for Chartism peaked at times of economic depression and hunger, in 1839, 1842 and 1848. In 1842, for example there was rioting in Stockport, due to unemployment and near-starvation, the new union workhouse was attacked. Also in Manchester workers protested against wage cuts, wanting ‘a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s labour’. The ‘Plug Plots’ were a series of strikes in Lancashire, Yorkshire, the Midlands and parts of Scotland that took place in the summer of 1842. Workers removed the plugs from the boilers in order to bring factory machinery to a halt. Wage cuts were the main issue, but support for Chartism was also strong at this time. In 1848 as trade was still depressed and interest in political reform peaked again with news of revolution in France and a third Chartist petition was planned.

Chartism is often described as a working class movement, but it had some middle class supporters who were hoped it would promote education reform and teetotalism. It was not necessarily a revolt against industrialization either. Many chartist supporters worked in the domestic industry as handloom weavers, stocking makers, shoemakers or carpenters; however, the latter two trades were not impacted by industrialization at that point.

Although the Chartist movement ended without achieving its aims, the fear of civil unrest remained. Later in the century, many Chartist ideas were included in the Reform Acts of 1867 and 1884. At the time, the six point charter proved too radical for a Parliament representing the middle and upper classes to make into law.

Possibly the movement could have made more progress had its leadership been more united. There were also regional differences in the nature of Chartist support, for example in Wales, Chartism was often associated with Nonconformist chapels but in Leeds some Chartists worked to enter local government. Despite its failure, it was a significant movement because it gave the working classes a sense of class consciousness and valuable political experience in campaigning, organizing publicity and holding meetings.

Text is a remix of “What was Chartism?” from The National Archives, licensed under Open Government Licence v.3.0 for Public Sector Information.