Radio History Snapshots

Broadcast turns 100: from the Hindenburg disaster to the Hottest 100, here’s how radio shaped the world

Wiki Commons, CC BY Peter Hoar, Auckland University of Technology

Eighty-one years ago, a broadcast of Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds supposedly caused mass hysteria in America, as listeners thought Martians had invaded New Jersey. There are varying accounts of the controversial incident, and it remains a topic of fascination, even today. Back when Welles’s fictional Martians attacked, broadcast radio was considered a state-of-the-art technology. And since the first transatlantic radio signal was transmitted in 1901 by Guglielmo Marconi, radio has greatly innovated the way we communicate.

Dots and dashes

Before Marconi, German physicist Heinrich Hertz discovered and transmitted the first radio waves in 1886. Other individuals later developed technologies that could send radio waves across the seas.

At the start of the 20th century, Marconi’s system dominated radio wave-based media. Radio was called “wireless telegraphy” as it was considered a telegraph without the wires, and did what telegraphs had done globally since 1844. Messages were sent in Morse code as dots and dashes from one point to another via radio waves. At the time, receiving radio required specialists to translate the dots and dashes into words.

SOS: the Titanic sinks

By 1912, radio was used to run economies, empires and armed forces. Its importance for shipping was obvious – battleships, merchant ships and passenger ships were all equipped with it. People had faith in technological progress and radio provided proof of how modern machines benefited humans. However, the sinking of the Titanic that year caused a crisis in the world’s relationship with technology by revealing its fallibility. Not even the newest technologies such as radio could avoid disaster.

Wiki Commons

Some argue radio use may have increased the ship’s death toll, as the Titanic’s radio was outdated and wasn’t intended to be used in an emergency. There were also accusations that amateur “ham radio” operators had hogged the bandwidth, adding to an already confusing and dire situation. Nonetheless, the Titanic’s SOS signal managed to reach another ship which led to the rescue of hundreds of passengers. Radio remains the go-to medium when disasters strike.

Making masts and networks

The more refined technology underpinning broadcast radio was developed during the First World War, with “broadcast” referring to the use of radio waves to transmit audio from one point to many listeners. Broadcast radio got traction in the early 1920s and spread like a virus. Governments, companies and consumers started investing in the amazing new technology that brought the sounds of the world into the home.

Huge networks of transmitting towers and radio stations popped up across continents, and factories churned out millions of radio receivers to meet demand. Some countries started major public broadcasting networks, including the BBC. Radio stations sought ways around regulations and, by the mid 1930s, some broadcasters were operating stations that generated up to 500,000 watts. One Mexican station, XERA, could be heard in New Zealand.

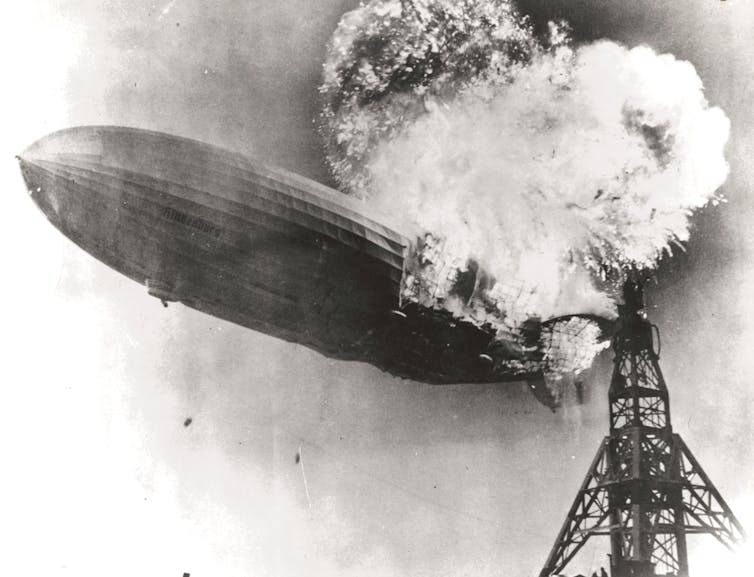

Hearing the Hindenburg

On May 6, 1937, journalist Herbert Morrison was experimenting with recording news bulletins for radio when the Hindenburg airship burst into flames. His famous commentary, “Oh the humanity”, is often mistaken for a live broadcast, but it was actually a recording.

Recording technologies such as transcription discs, and later magnetic tape and digital storage, revolutionized radio. Broadcasts could now be stored and heard repeatedly at different places instead of disappearing into the ether.

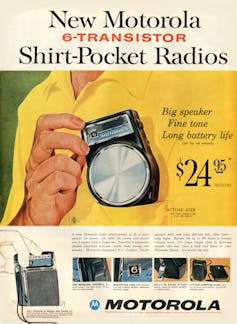

Transistors and FM

In 1953 radios got smaller, as the first all transistor radio was built.

Wiki Commons

Transistor circuits replaced valves and made radios very cheap and portable. Along with being portable, radio sound quality improved after the rise of FM broadcasting in the 1960s. While both FM and AM are effective ways to modulate carrier waves, FM (frequency modulation) offers better audio quality and less noise compared to AM (amplitude modulation). Music on FM radio sounded as good as on a home stereo. Rock and roll and the revolutionary changes of the 1960s started to spread via the medium. AM radio was reserved for talkback, news, and sport.

Beeps in space

In 1957, radio experienced lift-off when the USSR launched the world’s first satellite. Sputnik 1 didn’t do much other than broadcast a regular “beep” sound by radio. But this still shocked the world, especially the USA, which didn’t think the USSR was so technologically advanced. Sputnik’s beeps were propaganda heard all round the world, and they heralded the age of space exploration.

The launch of Sputnik 1 started the global space race. Today, radio is still used to communicate with astronauts and robots in space. Radio astronomy, which uses radio waves, has also revealed a lot about the universe to astronomers.

Digital, and beyond

Meanwhile on Earth, radio stations continue to use the Internet to extend their reach beyond that of analogue technologies. Social media helps broadcasters generate and spread content, and digital editing tools have boosted the possibilities of what can be done with podcasts and radio documentaries. The radio industry has learnt to use digital plenitude to the max, with broadcasters building archives and producing an endless flood of material beyond what they broadcast.

In 2020, organized broadcast radio turned 100. These days it’s considered a basic technology, but that may be why it remains such a vital medium. Media such as movies, television, the internet and podcasts were expected to sound its death knell. But radio embraces new technology. It survives, and advances.![]()

Peter Hoar, Senior Lecturer, School of Communications Studies, Auckland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons Attribution NoDerivatives 4.0 International license. Read the original article.