News Literacy Q&As

This chapter provides answers to a number of pertinent news literacy questions.

Q: How can a reporter answer all the key questions in a short article?

Journalistic writing is direct, concise and precise. As “The Elements of Style” says: “A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts.”

This book is to writing as “The Elements of Journalism” is to the reporting—a treatise, a bible, an instruction guide.

This semi-humorous video might help you remember the rules of writing short and concisely. The Elements of Style from Jake Heller on Vimeo.

The goal isn’t sentences that fall flat on the ear, but efficient and exacting word choices. I tell journalism students to pretend that there is a word drought; use as few words as possible to say what you need to say. You don’t water your lawn needlessly during a rain drought, and you don’t waste words in journalism. “This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline,” William Strunk, Jr. writes in the book, “but that every word tell.”

In addition to word choice, the article’s structure helps readers learn everything they need to know in a short amount of space.

There are three main story outlines journalists use in their articles: the kabob, the martini glass (or hourglass) and the inverted pyramid. The inverted pyramid is the most popular for short news stories because the focus is putting the most important information at the top (the widest part of the pyramid) and the least important at the bottom.

News wasn’t always written this way. If you compare articles written in the early 1800s to those written at the end of the century, you’ll notice the earlier ones are wordy, flowery and take forever to get to the point. What changed? The invention of the telegraph in 1845. “The thing to know about the telegraph is that in its day it was as revolutionary as the Internet,” writes Chip Scanlon in a 2003 article. This groundbreaking invention allowed newspapers to publish stories days after an event happened, not weeks or months. It also cost about 1 penny a character, which is the equivalent of $.34 today.

If you were a publisher and the above paragraph (606 characters) was going to cost you $207.04 to publish, wouldn’t you demand that your writers were as efficient as possible with their word choice?

This section is republished from News Literacy Now licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license. Read the original article.

Q: Why don’t journalists just stick to the facts?

Journalists get this question—or lament—all the time from people who think the news offers too much opinion and not enough fact. More than two-thirds of Americans say they see too much opinion and bias in news that is supposed to be “objective,” according to a Knight Foundation poll. Hence the plea, “just stick to the facts.”

Here’s the problem: Serving up just the facts can misrepresent the news or even create a false narrative. Facts need context—that background information that adds depth to a story and helps news consumers understand the issue or the wider implications of those facts. Context provides historical information and a frame of reference for comparisons. It’s necessary to make sense of the news.

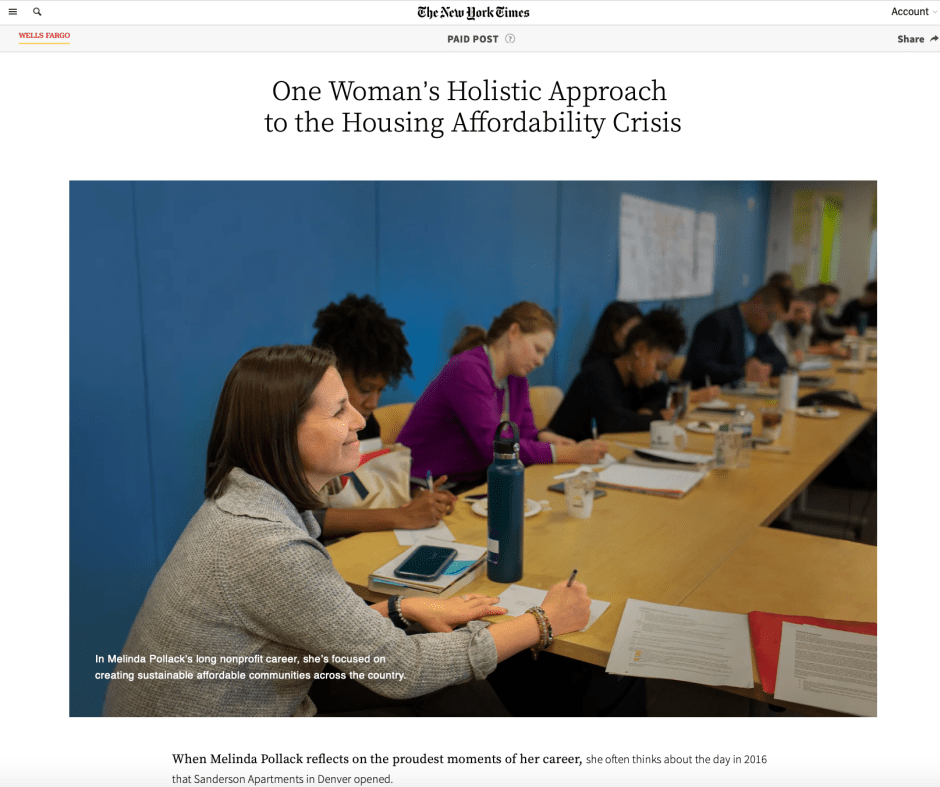

When context is missing, the truth can be distorted. Case in point: Supreme Court nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson’s record on sentencing sex offenders. Missouri Senator Josh Hawley has portrayed Jackson as “soft on crime” based on her sentences in seven child pornography cases that he listed in a thread on his Twitter account.

Several news outlets picked up on these tweets and published stories with headlines like “Ketanji Brown Jackson’s worrying, outdated thinking on child pornography” at the Washington Examiner, “An Alarming Pattern” on Daily Caller and “Hawley Warns of Biden’s SCOTUS pick’s ‘long record’ of letting child porn offenders off the hook” at Fox News.

Even network news outlets like NBC and CBS included Hawley’s claims in stories without “pushback, providing unchecked airtime to his lie about Jackson’s judicial record,” according to Mediamatters.org.

While Hawley accurately lays out the specifics of each case, the facts belie Jackson’s true record.

Why? Because they are presented without any context.

Jackson made more than 100 sentencing decisions and 500 rulings as a federal trial court judge on the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia since 2013. She presided over 14 child sex crime cases during that period. Those seven cases presented by Hawley are a small subset of her sentencing decisions and a judgment on whether she is “soft” or “tough” on crime should look at her record in its entirety, not a few cherry-picked cases.

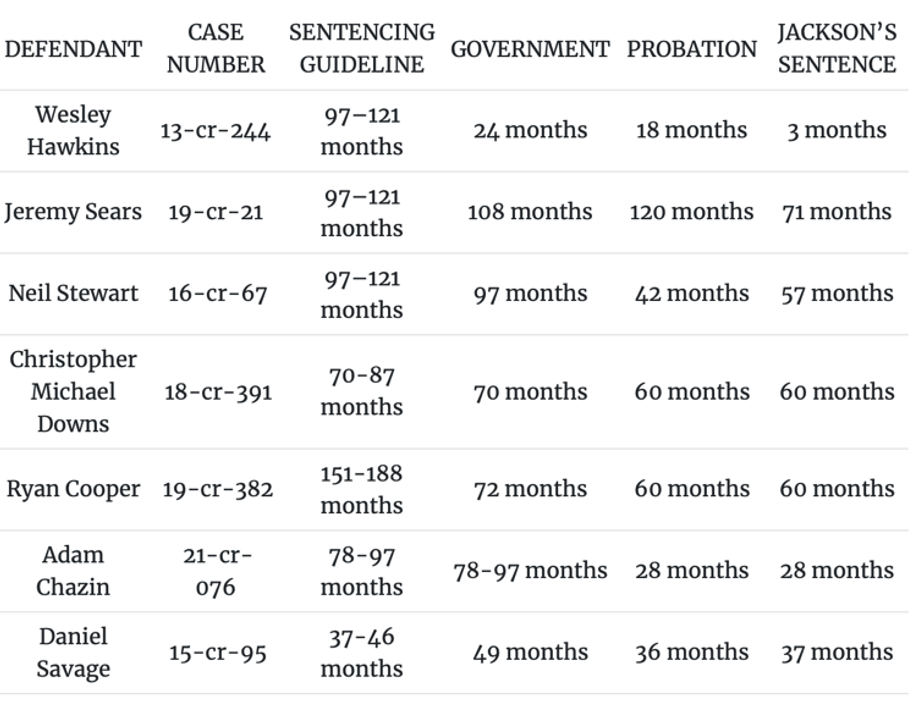

That said, in the seven cases listed below, Fact-check.org found that Jackson’s average sentence in these sex offender cases was more than two years below the minimum federal guidelines. That is a fact, but one that requires context to fully understand its relevance and meaning.

According to a 2021 report by the U.S. Sentencing Commission, 59 percent of all sentences for defendants in child pornography cases were below these minimum sentencing guidelines, largely because the legal community views the recommendations as excessively severe and in need of reform. In two of the seven cases, even the federal prosecutor recommended sentences below the minimum guideline. If this is considered, Jackson’s decisions on sentencing in these cases appear to be well within the mainstream.

The chart also includes the sentence recommended by the probation office, which provides all judges with a presentence report. Hawley neglected to mention that Jackson’s sentences in five of the seven cases aligned with, or exceeded, the probation office’s recommendation. Jackson’s sentences were below the government and probation office’s recommendations in just two cases.

In light of this context, both conservative and liberal legal scholars and numerous fact-checking sites have determined that Hawley’s charges that Jackson is “soft on crime” and “soft on sex offenders who prey on children” are misleading. Despite Hawley’s presentation of the facts in these cases, Fox News legal analyst Andrew McCarthy called the charges “a smear” and “meritless to the point of demagoguery,” and NYU law professor Rachel Barkow said Hawley’s claims misrepresent Jackson’s record and lack critical context.

In The Elements of Journalism, Kovach and Rosenstiel state that it is the journalist’s responsibility to verify information and then help make sense of it. They write that providing context “implies doing more reporting, adding facts, widening the lens and perspective. It is not argument or persuasion. Nor is it telling people what to think.” On the contrary, once news consumers are armed with the facts and the context surrounding those facts, they are in a position to reach their own informed opinion.

Kovach and Rosenstiel go on to say the truth is a complicated and sometimes contradictory phenomenon and that, fortunately, journalists have moved beyond stenography. Brent Cunningham’s 2003 essay Re-Thinking Objectivity notes that American reporters began to question “official” narratives during the 1960s and ‘70s, and quotes former New York Times reporter Anthony Lewis: “Vietnam and Watergate destroyed what I think was a genuine sense that our officials knew more than we did and acted in good faith.” To this, Cunningham adds that journalists began to appreciate the “limits of objectivity,” noting that “reporters [are allowed] leeway to analyze, explain, and put news in context, thereby helping guide readers and viewers through the flood of information.”

Facts alone cannot guide us through that flood. As Cunningham observes, context is the ingredient that transforms facts into knowledge and ultimately, truth.

This section is republished from News Literacy Now licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license. Read the original article.

Q: What is the difference between news and truth?

Men were dying. Homeless, indigent, alone, often asleep on city streets or in subway cars. No one knew when the next death might occur. The locations were adding up, too: Washington, then New York. Was Boston next? Baltimore? Fear gripped the eastern seaboard, especially among those with nowhere to go but the subways and streets. A serial killer was on the loose. Why homeless men were the target, no one knew.

It was up to the daily crime reporters in New York and Washington to report these deaths, to follow the story as it developed. We all relied on those reports. They gave us the news practically in real time. They let us know when the killing in one city seemed to abate, only to resume in another a few hours away by train. To those old enough to have lived through past killing sprees, like that of the DC sniper in 2002 or those of the Son of Sam in 1976-77, the first two weeks of March 2022 felt terrifyingly familiar.

That’s the news. It gives us essential information. Often that information gets richer as the story develops. By March 15th, a suspect had been arrested: Gerald Brevard III. We learned details about his life, his past arrests, his history of mental illness. More news, more context. The story grew.

By March 21st, we knew more about two of the men Brevard allegedly killed. The story evolved from being about a serial killer on the loose to one about a suspect in custody to one about the scourge of mental illness. The two victims suffered from delusions. Brevard was not homeless or indigent, but he too suffered from mental anguish. The reporting became less alarming and more humane. A search of Brevard’s apartment uncovered writings by the suspect that suggest a loosening grip on reality: “I write a poem, now I’m a poet. Can’t kill her I love her, she’ll never know it. Even when guilty I’m innocent.”

The story isn’t over; Brevard has yet to stand trial. Nevertheless, we can begin to look at the big picture: How and why does our society continue to fail the mentally ill? Answering that will take time, and it will demand a lot more than beat reporters telling us about the latest death in a major American city. It will require a long, hard look at an inconvenient truth about this country: For all its prosperity, America does not take sufficient care of its most vulnerable. Sometimes, as the March killings suggest, this has tragic consequences.

In 2003, Brent Cunningham wrote an essay for the Columbia Journalism Review titled Re-thinking Objectivity. In it, he argues that journalistic “objectivity” is not only a myth, but a dangerous one that leads us into situations like the war in Iraq. In the lead-up to that war, Cunningham notes that very few publications spent any time addressing the ramifications of invading Iraq. Instead, they focused on the tick-tock of what the Bush administration was doing and saying about its plans to invade. There was scant analysis, zero speculation. Only the official word from the White House. This makes sense: Unless they’re commentators, journalists are not supposed to speculate, but to report the news. If the president says something, they report it.

But in fixating so much on the facts of the present, Cunningham writes, they failed to address the inevitable truth of the future: Invading Iraq would create a quagmire from which we might never emerge. “Our pursuit of objectivity can trip us up on the way to ‘truth,’” Cunningham writes. “Objectivity excuses lazy reporting. If you’re on deadline and all you have is ‘both sides of the story,’ that’s often good enough.”

He continues: “It’s not that such stories laying out the parameters of a debate have no value for readers, but too often, in our obsession with, as The Washington Post’s Bob Woodward puts it, ‘the latest,’ we fail to push the story, incrementally, toward a deeper understanding of what is true and what is false.”

What does this have to do with Gerald Brevard and the men he is accused of having killed? Surely, we would not want to dispense with the daily reporting that began on March 3rd and ended on March 12th, the dates that bookend his killing spree in New York and Washington. We needed that coverage. It was the news. But if we stop there, we ignore the systemic problems that led to those deaths. We pretend that events happen in a vacuum. We ignore the truth.

To be sure, grappling with the Truth (capital T) is not the job of daily journalists. After all, truth is complex, debatable, and often subjective. But, as Cunningham argues, the most seasoned journalists can bring their expertise and analysis to the table, let it inform their reporting, and inch us toward a deeper understanding of important social and political issues like mental illness, poverty, drug addiction, and war. Otherwise, all we’ve got is the news.

This section is republished from News Literacy Now licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license. Read the original article.

Q: What’s the problem with native advertising? Should news outlets limit this content?

One of the biggest challenges news consumers face today is distinguishing news from other media that does not embody journalism’s three defining attributes: Verification, independence and accountability. Thanks to native advertising, the line between news and advertising has never been more blurred. By design, native ads look just like news stories, blending in seamlessly with editorial content. And therein lies the problem.

Nearly all consumers are easily and consistently duped by native ads, according to research by Boston University Professor Michelle Amazeen. In her study, she showed 738 participants a Bank of America native ad seen below called “America’s Smartphone Obsession Extends to Mobile Banking,” which included a disclosure at the end identifying it as an ad. Despite this label, more than 9 in 10 people thought they were reading a news article with unbiased and vetted information.

Old school journalists (like me) are wary of native ads because they undermine the public’s already wavering trust in the news media. When Amazeen disclosed that the Bank of America article was actually an ad, participants reacted negatively and blamed the news media for spreading fake news. “Trust in media is at an all-time low,” said Amazeen in a Phys.org article. “I’m not suggesting it’s only from native advertising, but I think it’s a contributing factor.”

Also not a fan of this paid content, John Oliver, who devoted an entire segment of his show Last Week Tonight to bashing these ads. “Native ads are baked into content like chocolate chips into a cookie. Except it’s more like raisins in a cookie because no one f**cking wants them there,” said Oliver.

Advertising firms and the business side of many news sites would disagree with that last part. Native advertising is a lucrative business, topping more than $85 billion in 2020, according to ADYOULIKE, a global native advertising platform. BuzzFeed News was one of the first to profit from ads that look like news, but its success led others to embrace a much-needed new revenue source.

In 2013, the Washington Post set up its WP BrandConnect business to produce sponsored content. Then, in 2016, the New York Times followed with T Brand Studio. As word spread that native ads were more effective and engaging than traditional ads, demand grew, and The Wall Street Journal, Boston Globe, The Atlantic, and Politico, to name just a few, set up teams to create paid content. Now nearly all news sites profit from native advertising despite the risks to their credibility and integrity.

And no one is talking about limiting this content. To the contrary, native ad spending is expected to grow to more than $400 billion by 2025. That means it’s going to be even more pervasive and that we had all better learn how to tell the difference between paid and unpaid content.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC), a bipartisan agency responsible for protecting consumers from deceptive advertising practices, has issued guidelines calling for clear and prominent labels such as “Advertisement,” “Paid Advertisement,” “Ad” or “Sponsored Advertising Content” rather than “Promoted” or “Presented By,” which can be misleading.

And most reputable news sites have produced their own guidelines as well. After the backlash following The Atlantic’s native ad clearly endorsing the Church of Scientology, it came up with a comprehensive set of guidelines that reads in part:

- The overriding consideration is that The Atlantic must maintain its editorial integrity and the trust of its readers.

- All advertising content must be clearly distinguishable from editorial content. To that end, The Atlantic will label an advertisement with the word “Advertisement” when, in its opinion, this is necessary to make clear the distinction between editorial material and advertising.

- As with all advertising, and consistent with the foregoing General Advertising Guidelines, The Atlantic may reject or remove any Sponsor Content at any time that contains false, deceptive, potentially misleading, or illegal content.

That may sound all well and good, but in reality, many of these ”clearly distinguishable” labels are easy to overlook or ignore. That leaves the onus, once again, on news consumers to be vigilant because no one can afford to take any content at face value in this digital age.

This section is republished from News Literacy Now licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license. Read the original article.

Q: What’s the appeal of conspiracy theories?

Humans are storytellers. We like narratives that take the random chaos of life and put it into a coherent structure. The alternative is too difficult to live with: a world where nothing adds up to anything, nothing results from anything else, and people are just free-floating organisms in a sea of other organisms with nothing to connect them. Even history is just a way to make sense of life and is far more creative and subjective than most elementary and high school textbooks acknowledge.

But when we tell stories to make sense of real events, we have two options: fabricate and make connections based on speculation or research what happened and form narratives based on facts.

In a nutshell, this is the difference between a conspiracy theory and an actual conspiracy. In recent years, the extraordinary growth of social media has enabled the former to spread more rapidly than ever before, to take root in communities, and to undermine efforts by scientists, journalists and others to inform the public with credible information. The most prevalent example today is QAnon, the conspiracy theory that a high-level intelligence officer has been leaking highly classified information about “deep-state Democrats” controlling society from the shadows and even trafficking children for sex.

In 2016, just before a user with the name QAnon appeared for the first time on message boards, a man named Edgar Welch drove from North Carolina to Washington, D.C., with a carload of artillery, intending to liberate children from the basement of a pizza parlor called Comet Ping Pong. Welch had read about an alleged sex-trafficking operation on social media and decided to take matters into his own hands. The idea that Democrats, with all their power and ties to big industry, were abusing children on top of everything else was too much for Welch to bear.

But when he arrived and even fired a round inside the restaurant, he found no children. Police arrested Welch at the scene, and he is now in prison for numerous offenses. None of them, however, is believing in the conspiracy theory. That’s because simply believing conspiracy theories is not illegal; in fact, QAnon believers have even been elected to Congress. No one is saying that believing in conspiracy theories should be illegal, but we need to do more to understand their popularity and their spread.

So what’s the difference between a conspiracy theory and a real conspiracy? Basically, a real conspiracy would hold up under scrutiny. One example is Bridgegate, a scandal from 2013 in which New Jersey government officials conspired to shut down part of the George Washington Bridge as a way to punish the mayor of Fort Lee, a Democrat, for not supporting the Republican governor, Chris Christie. A local reporter broke the story by starting with some very simple questions, like “Why is there so much congestion on the bridge if no work is being done?” He ultimately uncovered a plot involving numerous people close to Christie to put pressure on the Fort Lee mayor, and eventually, the facts came to light. By reporting the story, he showed that the connections were not mere coincidence or speculation.

Researchers at UCLA recently did a study on conspiracy theories and found that this is the key difference between a theory and an actual conspiracy. If you sever any major connection in a conspiracy theory, the whole thing falls apart. But if you sever a connection in a real conspiracy — that is, if you prove that two people who were alleged to have had a secret meeting, for example, have never met — then further investigation will show that other connections nevertheless exist. A conspiracy theory would fall apart the moment such a connection was severed. In other words, everything has to line up exactly as the conspiracy theorists say, even without direct evidence to back up their claims.

And yet, many people believe in conspiracy theories. The reason is very simple, and it goes back to the beginning of this post: They explain the unexplainable. We may never know, conclusively, where the coronavirus originated, who the first infected person was, or how it mutated early on to become even more deadly than it might have been otherwise. And that’s tough to sit with, the not knowing. Conspiracy theories like the notion that the virus was developed in a lab and intentionally leaked into the population, and then spread around the world with the help of Bill Gates so that he could plant tracking technologies in our bodies through vaccine injections, may sound ludicrous to some. But to others, such a theory is much more palatable than living with not knowing.

The problem is not our natural tendency to seek out structure but our inability to discern facts from fiction. That’s where critical thinking comes in. We need to be able to separate credible information from fabrication; we need facts to navigate life. If we believe in fictions, we risk nothing less than life itself–of ourselves, our loved ones, and the well-being of the planet.

This section is republished from News Literacy Now licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license. Read the original article.