Public Relations Basics

Parts of this chapter remixed from Curation and Revision provided by: Boundless.com is licensed under a Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

What is Public Relations?

Whereas advertising is the paid use of media space to sell something, public relations (PR) is the attempt to establish and maintain good relations between an organization and its constituents (Theaker, 2004). Practically, PR campaigns strive to use the free press to encourage favorable coverage. In their book The Fall of Advertising and the Rise of PR, Al and Laura Ries make the point that the public trusts the press far more than they trust advertisements. Because of this, PR efforts that get products and brands into the press are far more valuable than a simple advertisement. Their book details the ways in which modern companies use public relations to far greater benefit than they use advertising (Ries & Ries, 2004). Regardless of the fate of advertising, PR has clearly come to have an increasing role in marketing and ad campaigns.

The Public Relations Society of America (PRSA) defines public relations as “a strategic communication process that builds mutually beneficial relationships between organizations and their publics” (2016, para. 4). Simply put, public relations helps to influence an audience’s perceptions by building relationships and shaping public conversations about a client or company. These public conversations often take place through mass media and social media, which is why public relations professionals need to understand how to work with and write effective messages for the media.

Public relations professionals are in charge of a wide range of communication activities that may include increasing brand visibility and awareness, planning events, and creating content. Some of them also deal with crisis communication and help to salvage a brand’s integrity and reputation during a negative event. This video from Kate Finley, chief executive officer of Belle Communications, explains what it is like to work at a public relations agency.

What to Expect from a PR Agency with Kate Finley

Video Clip

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_av8i27di04

The History of PR And Propaganda

At the core of PR is a simple model developed by Harold Lasswell in the 1940s. Developing an effective PR model was an important war effort during World War II when it was essential to develop theories for how propaganda worked to determine what the Nazis were doing and, if possible, how their propaganda could be stopped. Lasswell’s model asked five simple questions: who (Sender) sent what (Message) through which channel (Channel) to which audience (Receiver) and with what effect. This was a way of breaking down mass influence beyond advertising. In a sense, governmental propaganda is PR, but the client is a country. The S-M-C-R model (often attributed in that particular configuration to Berlo) is the most efficient model for understanding how to break down and analyze messages in the mass media.

Professionals and academics examine and manipulate all four components to isolate which changes correlate with which behavioral effects. S-M-C-R assumes that the sender comes first and the receiver comes last. There is a time element that must be established in researching the effects of mass-mediated messages, but the point is that this simple model of propaganda became the basis for all sorts of media effects studies. Propaganda and PR messaging do not work immediately to bring about drastic changes in behavior. Behavioral phenomena, particularly changes in behavior, are driven by many variables however, if you want to begin to look at an advertising campaign, film, or news documentary to examine its effects, this is the model to start with.

Noise must be accounted for, and in an age dominated by the digital information glut, the opportunity for immediate feedback and engagement must also be considered. Receivers almost immediately become senders in a network. Thus, the S-M-C-R model will often include measures looking at how much noise gets into the system and looking at what happens when receivers immediately start their own S-M-C-R processes. Wherever a message originates, even if it is as simple as clicking “Share” on Facebook, the S-M-C-R model starts again.

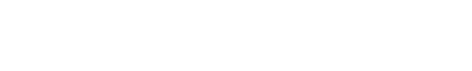

Four Models Of Public Relations

Grunig and Hunt (1984) developed four models of public relations that describe the field’s various management and organizational practices. These models serve as guidelines to create programs, strategies, and tactics.

In the press agent/publicity model, communications professionals use persuasion to shape the thoughts and opinions of key audiences. Under the traditional publicity model, PR professionals seek to create media coverage for a client, product, or event. These efforts can range from wild publicity stunts to simple news conferences to celebrity interviews in fashion magazines. P. T. Barnum was an early American practitioner of this kind of PR. His outrageous attempts at publicity worked because he was not worried about receiving negative press; instead, he believed that any coverage was a valuable asset. In this model, accuracy is not important and organizations do not seek audience feedback or conduct audience analysis research. It is a one-way form of communication. One example is propagandist techniques created by news media outlets in North Korea.

The public information model moves away from the manipulative tactics used in the press agent model and presents more accurate information. The goal of the public information model is to release information to a constituency. This model is less concerned with obtaining dramatic, extensive media coverage than with disseminating information in a way that ensures adequate reception. For example, utility companies often include fliers about energy efficiency with customers’ bills, and government agencies such as the IRS issue press releases to explain changes to existing codes. In addition, public interest groups release the results of research studies for use by policy makers and the public. However, the communication pattern is still one-way. Practitioners do not conduct audience analysis research to guide their strategies and tactics.

The two-way asymmetrical model presents a more “scientifically persuasive” way of communicating with key audiences. Here, content creators conduct research to better understand the audience’s attitudes and behaviors, which in turn informs the message strategy and creation. To be considered effective, this model requires a measured response from its intended audience. Government propaganda is a good example of this model. Propaganda is the organized spreading of information to assist or weaken a cause (Dictionary). Edward Bernays has been called the founder of modern PR for his work during World War I promoting the sale of war bonds. One of the first professional PR experts, Bernays made the two-way asymmetric model his early hallmark. In a famous campaign for Lucky Strike cigarettes, he convinced a group of well-known celebrities to walk in the New York Easter parade smoking Lucky Strikes. Persuasive communication is used in this model to benefit the organization more so than audiences; therefore, it is considered asymmetrical or imbalanced. Most modern corporations employ the persuasive communication model. The model is particularly popular in advertising and consumer marketing, fields that are specifically interested in increasing an organization’s profits.

Finally, the two-way symmetrical model argues that the public relations practitioner should serve as a liaison between the organization and key publics, rather than as a persuader. The two-way symmetric model requires true communication between the parties involved. By facilitating a back-and-forth discussion that results in mutual understanding and an agreement that respects the wishes of both parties. Here, practitioners are negotiators and use communication to ensure that all parties involved benefit, not just the organization that employs them. The term “symmetrical” is used because the model attempts to create a mutually beneficial situation. This PR model is often practiced in town hall meetings and other public forums in which the public has a real effect on the results. In an ideal republic, Congressional representatives strictly employ this model.

Many nonprofit groups that are run by boards and have public service mandates use this model to ensure continued public support. Commercial ventures also rely on this model. PR can generate media attention or attract customers, and it can also ease communication between a company and its investors, partners, and employees. The two-way symmetric model is useful in communicating within an organization because it helps employees feel they are an important part of the company. Investor relations are also often carried out under this model. The two-way symmetrical model is deemed the most ethical model, one that professionals should aspire to use in their everyday tactics and strategies (Simpson, 2014).

Some experts think of public relations more broadly. For instance, they may argue that political lobbying is a form of public relations because lobbyists engage in communication activities and client advocacy in order to shape the attitudes of Congress (Berg, 2009).

Why Do Companies Need Public Relations?

The history of the public relations field is often misunderstood. Many think of public relations as organized manipulation made up of corporate, political and even non-profit propaganda. It is often thought of as deception, but this is not always the case. In a society fueled by networked communications, it is becoming less important to ask what messages people receive and more important to ask what messages they seek out, according to Greg Jarboe, author of a brief history of PR. Jarboe worked for a PR firm with offices in San Francisco and Boston, two of the most well-established technology markets in the country. He argues that PR is more about creating a sense of understanding between consumers and brands and that this might be done just as well by the brand in digital spaces just as it is via other mass media channels controlled by other corporate entities. Historically, PR depended on other media platforms such as TV, newspapers and magazines to promote its content. Content marketing means this is no longer the case. Mass media platforms may still be needed to reach mass audiences outside of a brand’s collection of fans and followers, but much goodwill can be generated by maintaining a proactive, positive and professional digital presence.

While it is true that PR often tries to put a good face on companies with all manner of reputations and harmful business practices, it also serves charities, governmental services and small local businesses. Not every institutional organization can have a huge PR budget, but the practices can be taught to just about any small business owner.

There was a time when many companies did not see the value of public relations, unless a crisis happened. Even now, some public relations professionals face challenges in convincing key executives of their value to the function of the company.

With the abundance of information readily available to audiences worldwide, companies are more vulnerable than ever to misinformation about their brand. An audience’s attitudes and beliefs about a company can greatly influence its success. Therefore, the public relations professional helps to monitor and control conversations about a company or client and manage its reputation in the marketplace. Viewing public relations as a key management function of a business or an essential strategy to manage one’s individual reputation will help accomplish important goals such as establishing trust among key publics, increasing news media and social media presence, and maintaining a consistent voice across communication platforms.

For more on the impact of reputation on business success, take a look at this article from The Entrepreneur.

Public Relations Versus Marketing Versus Advertising

Many people confuse public relations with marketing and advertising. Although there are similarities, there also are key differences.

Probably the most important difference between marketing, public relations, and advertising is the primary focus. Public relations emphasizes cultivating relationships between an organization or individual and key publics for the purpose of managing the client’s image. Marketing emphasizes the promotion of products and services for revenue purposes. Advertising is a communication tool used by marketers in order to get customers to act. The image below outlines other differences.

MARKETING

- Systematic process and planning of an organization’s promotional efforts

- Larger umbrella term that includes public relations and advertising

- Focused on the promotion of products and/or services in order to drive sales

- Audience is primarily customers or potential buyers

- Paid media: companies have to pay for marketing efforts

P.R.

- Focused on creating a favorable public image through relationship building and reputation management

- Draws attention to public conversations and media coverage. Also diverts attention away from public discussions if damaging.

- Audiences varies; not just customers (examples: media, internal employees)

- Component of marketing

- Earned media: Publicity achieved through pitching or convincing journalists to cover your client or organization

ADVERTISING

- Focused on drawing attention to the product through strategic placement and imagery

- Component of marketing (falls under the umbrella of marketing efforts)

- Execution of some marketing plans

- Paid media: companies have to pay for advertisement creation

- Audience is primarily customers or potential buyers

For more information on the differences between marketing, public relations, and advertising, read the following article:

Content Marketing

Content marketing refers to a common practice where brands produce their own content, or hire someone else to produce it, and then market that information as an alternative to advertising. It still moves people along the purchase funnel, but there is usually added value in this type of content. If an advertisement for a mattress describes its features and price, a blog funded by the mattress brand might compare the pros and cons of many different mattresses, perhaps with a bias toward the brand. It isn’t always pretty. Content produced for a brand should ethically be labeled as sponsored, but it is not always done. In cases when consumers have discovered that trusted sources were content marketers rather than independent reviewers, the revelations have created public relations problems for the brands. Content marketing done ethically offers financial transparency while providing valuable information and an emotional connection to the product for consumers. It can take the form of blog posts or entire blogs. Such marketing is usually optimized for search engines, which is to say the posts are written to attract search engine attention as well as outside links, which also alerts search engines that this content is valuable. Done well, branded content can be seen as more authentic than advertising content, and it can be cheaper to produce and disseminate. It is difficult to do well, of course.

The most common types of content created in this context besides blog content are social media profiles and posts, sponsored content in social media spaces, and even viral video and meme chasing. Brands might have their own social media profiles, or they might support social media influencers to promote their products in a sponsored way. Brands might also use their influencer teams or their own internal marketing teams to follow viral social media trends and to create memes. In a sense, content marketing allows a brand to create a more human profile in digital spaces. In this manner, brands can engage with potential and repeat customers. Brands can foster relationships and encourage brand advocacy among people not being paid to promote their products. Many brands use this form of marketing to engage consumers on a deep level and to offer information and emotion that might not be present in other forms of advertising.

More Concepts In PR

For most of the 20th century, the shorthand definition of PR was that it was like advertising only instead of paying a media outlet to run a message, you sent the message out to journalists and other gatekeepers in the hopes that they would share the information as news. Now, PR has to work in a digital media system where news reporters and editors are not the major gatekeepers deciding what information will be made public. PR professionals now need to think about search algorithms, search engine optimization, social media trends, social media platform algorithms, social media influencers, and social link sharing sites such as Reddit. Publicity on these channels can be worth tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars. PR often measures its worth in earned media — the amount of free air-time on TV or space in major newspapers and magazines that is earned by getting other mass media channels to tell your product’s stories without having to pay for ad space.

An example of earned media is when Apple released a new iPhone, and news organizations provided coverage of the lines that wrapped around city blocks as people waited for the latest gadget. For years, Apple earned millions of dollars in earned media by keeping new features a secret and then releasing new iPhones with considerable hype. Free marketing time and space in digital and print publications can help push a brand from being a leader to being legendary.

PR can take the form of an event, a product placement, or a skillfully crafted message delivered during a crisis. It is much less about promoting specific brands and more about promoting and maintaining the image of a brand, company or large corporation. Recall that advertising tends to focus on brands and products. PR can focus on the company and the corporate narrative, the story of how the company came to exist and how it represents certain values and ideals — at least in theory.

Sometimes it helps us to understand an element of mass media if we discuss when it all goes wrong. When British Petroleum (BP) had an oil gusher erupt in the Gulf of Mexico on April 20, 2010, after the Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded, 11 people died, and more than three million barrels of oil leaked into the gulf. It took almost three months to cap the oil gusher. The CEO of BP, Anthony Bryan “Tony” Hayward, lost his job because he made a major PR blunder when he said he just wanted his “life back.” Eleven people were dead. The fishing and tourism industries of Louisiana, Mississippi and parts of Texas, ravaged by hurricanes just years before, were being threatened again. This time, though, Mother Nature was not to blame. It was BP, a multinational corporation that up to that point had been working to create a more environmentally friendly image. It took BP years to come back from that disaster, and it was made worse because of poor crisis communications. PR is about promoting good relationships with your consumers, your employees and the communities where your products are made. It is about earning “free” news and social media coverage, but perhaps most importantly it is about managing crises so that people are not given a reason not to buy your products.

Crisis Management

The best way to build good PR is to carefully maintain a good reputation over time and to avoid behaviors as an individual, company, or corporation that might harm others. The best prevention against bad PR is to follow your industry’s and your own ethical codes at all times, whatever they are. Even if you do this, you might still face a PR crisis. For example, a politician might decide to target your brand regardless of whether your business practices are ethical. All the more reason to maintain good longstanding relationships with your consumers.

The first rule of crisis communications is to plan ahead by anticipating the kinds of problems your company might have. Chemical companies should prepare for chemical spills. Sports teams will probably not prepare for environmental disasters, but they may have to prepare for the social media scandals that players sometimes land themselves in. If there is a disaster, the advice is to “be truthful and transparent,” to not say too much, and to correct any exaggerations that emerge in the news media and on social media, within reason. Engaging in social media arguments is almost never productive for a brand, unless you have Wendy’s level of Twitter clapback. A major goal of PR efforts during a crisis is to try to make people forget there ever was a crisis.

Journalists often have the opposite interest because reporting on conflict is interesting. Helping people to survive is one of the primary functions of journalism. This explains why negative news gets so much more attention than positive news. No one dies when people do their jobs salting the roads and drivers maneuver safely in snowstorms. When people crash, that is news. Journalists know that people care about safety perhaps more than any other issue, so they focus on safety concerns during times of crisis. At these times, PR and journalism can be at odds, but truth and transparency are still advisable to the PR professional. You do not legally have to tell journalists everything that has happened (depending on the circumstances and whether your institution is funded by taxpayers), but if journalists discover a negative impact that you failed to disclose, they will wonder what else you are hiding, and they may give your critics and detractors extra consideration and attention.

PR professionals work to manage story framing. PR pros often work with journalists to cover negative stories with clarity and honesty rather than trying to hide the facts about a crisis. Finally, in PR there is the need to learn from mistakes and to analyze a company or corporation’s crisis responses. As difficult as it might be to go back and discuss where communication failed, it is essential. Reflection is a critical step in learning and corporations are like any other social institution. They need to learn to survive and to thrive.

PR Wars | PR And Advertising | PR And Marketing

Besides the conflict during crisis situations between journalists and PR professionals, there are PR battles that go on between competing brands and between non-profits, corporations and government officials all the time. Lobbyists make demands on politicians but also push agendas on mass media and social media platforms. In an age of digital communication, it is cheap and easy to develop detailed, professional messages employing a variety of media types that PR pros can try to spread around the world instantaneously. You should be aware as an information consumer that there are ongoing battles for your allegiance. Corporations engage in PR combat all the time, though they often try to work undetected. This is not to claim conspiracy or to frighten readers. It is simply a matter of fact that PR efforts are ongoing and that attacks within these battles do not always take the form of headlines. They may come in the form of messages from Twitter bots, botnets, collections of fake social media profiles run by software or blogs, or email spam.

You can influence other people by what you read and share, and you are encouraged once again to be aware of where your news sources get their information. Read and think before you share. It has become easy for individuals and fake accounts to publish information into the world’s information glut. Twitter and Instagram followers and Facebook friends can easily be bought. Major political influence is now wielded by fake accounts working to drum up anger and to promote misinformation to sway public opinion. Individual information consumers must take responsibility for their own consumption and for what they spread. Your media health is as important as your health. Protect yourself and those you share information with.

What you need to be able to do is to consider a source, consider how it is presenting its message, and consider the source’s sources. Media literacy is about what enters your mind: what stays in (that is, what is salient) and what goes out. We are all publishers now. Media, society, and culture will always influence you to some degree, but they are also yours to try to control. Mass audiences may be in decline, but entities who know how to build mass networks of users and how to successfully, if not always ethically, use their information are only starting to show their power.

PR Functions

Either private PR companies or in-house communications staffers carry out PR functions. A PR group generally handles all aspects of an organization’s or individual’s media presence, including company publications and press releases. Such a group can range from just one person to dozens of employees depending on the size and scope of the organization.

PR functions include the following:

- Media relations: takes place with media outlets

- Internal communications: occurs within a company between management and employees, and among subsidiaries of the same company

- Business-to-business: happens between businesses that are in partnership

- Public affairs: takes place with community leaders, opinion formers, and those involved in public issues

- Investor relations: occurs with investors and shareholders

- Strategic communication: intended to accomplish a specific goal

- Issues management: keeping tabs on public issues important to the organization

- Crisis management: handling events that could damage an organization’s image.

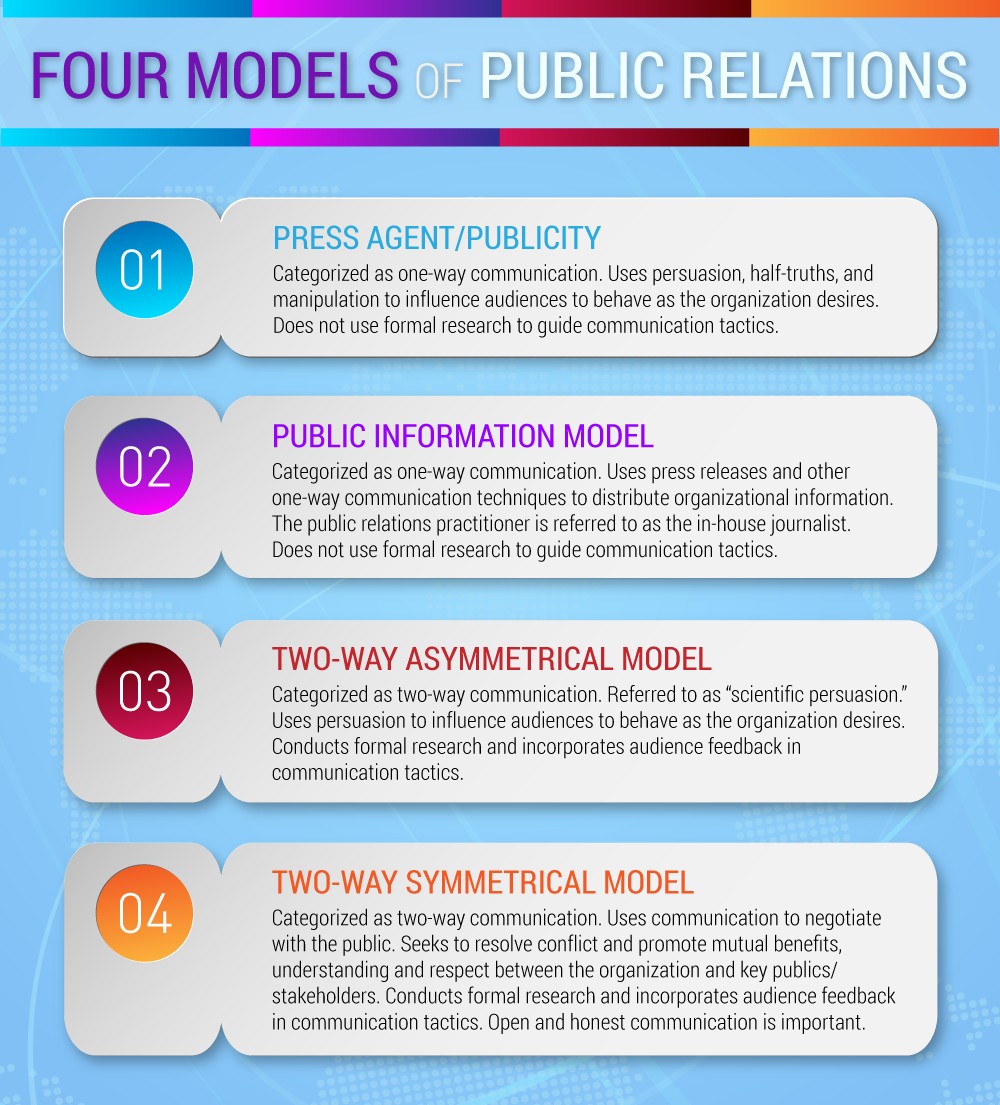

Anatomy of a PR Campaign

PR campaigns occur for any number of reasons. They can be a quick response to a crisis or emerging issue, or they can stem from a long-term strategy tied in with other marketing efforts. Regardless of its purpose, a typical campaign often involves four phases.

Initial Research Phase

The first step of many PR campaigns is the initial research phase. First, practitioners identify and qualify the issue to be addressed. Then, they research the organization itself to clarify issues of public perception, positioning, and internal dynamics. Strategists can also research the potential audience of the campaign. This audience may include media outlets, constituents, consumers, and competitors. Finally, the context of the campaign is often researched, including the possible consequences of the campaign and the potential effects on the organization. After considering all of these factors, practitioners are better educated to select the best type of campaign.

Strategy Phase

During the strategy phase, PR professionals usually determine objectives focused on the desired goal of the campaign and formulate strategies to meet those objectives. Broad strategies such as deciding on the overall message of a campaign and the best way to communicate the message can be finalized at this time.

Tactics Phase

During the tactics phase, the PR group decides on the means to implement the strategies they formulated during the strategy phase. This process can involve devising specific communication techniques and selecting the forms of media that best suit the message. This phase may also address budgetary restrictions and possibilities.

Evaluation Phase

After the overall campaign has been determined, PR practitioners enter the evaluation phase. The group can review their campaign plan and evaluate its potential effectiveness. They may also conduct research on the potential results to better understand the cost and benefits of the campaign. Specific criteria for evaluating the campaign when it is completed are also established at this time (Smith, 2002).

Public Relations Tools

Public relations (PR) is the practice of managing the flow of information between an individual or an organization and the public. The aim is to persuade the public, investors, partners, employees, and other stakeholders to maintain a certain point of view about the company and its leadership, products, or political decisions. Common PR activities include speaking at conferences, seeking industry awards, working with the press, communicating with employees, and sending out press releases.

Public relations may include an organization or individual gaining exposure to an audience through topics of public interest and news items. Building and managing relationships with those who influence an organization’s or individual’s audiences is critical in public relations. When a public relations practitioner is working in the field, they build a list of relationships that become assets, especially in media relations. The ultimate objective of PR is to retain goodwill as well as create it; the procedure to follow to achieve this is to first do good and then take credit for it. The PR program must describe its target audience—in most instances, PR programs are aimed at multiple audiences that have varying points of view and needs.

There are several PR tools firms can utilize to ensure the efficacy of PR programs: messaging, audience targeting, and media marketing.

Messaging

Messaging is the process of creating a consistent story around a product, person, company, or service. Messaging aims to avoid having readers receive contradictory or confusing information that will instill doubt in their purchasing choice or spur them to make other decisions that will have a negative impact on the company. A brand should aim to have the same problem statement, industry viewpoint, or brand perception shared across multiple sources and media.

Audience Targeting

A fundamental technique of public relations is identifying the target audience and tailoring messages to appeal to them. Sometimes the interests of different audiences and stakeholders vary, meaning several distinct but complementary messages must be created.

Stakeholder theory identifies people who have a stake in a given institution or issue. All audiences are stakeholders (or presumptive stakeholders), but not all stakeholders are audiences. For example, if a charity commissions a public relations agency to create an advertising campaign that raises money toward finding the cure for a disease, the charity and the people with the disease are stakeholders, but the audience is anyone who might be willing to donate money.

Media Marketing

Digital marketing is the use of Internet tools and technologies, such as search engines, Web 2.0 social bookmarking, new media relations, blogs, and social media marketing. Interactive PR allows companies and organizations to disseminate information without relying solely on mainstream publications and to communicate directly with the public, customers, and prospects. Online social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter ensure that firms can get their messages heard directly and quickly. Other forms of media include newspapers, television programs, radio stations, and magazines. Public relations people can use these various platforms and channels to publish press releases. It is important to ensure that the information across all channels is accurate and as complementary as possible.

The amount of money spent on traditional media channels has declined as more and more readers have turned to favor online and social media news sources. As the readership of traditional media shift to online media, so has the focus of many in public relations. The advent and increase of social media releases, search engine optimization, and online content publishing and the introduction of podcasts and video are related trends.

Sponsorship is often used as part of a public relations campaign. A company will pay money to compensate a public figure, spokesperson, or “influencer” to use its logo or products. An example of sponsorship is a concert tour presented by a bank or drink company.

Product placement is basically passive advertising in which a company pays to have its products used prominently in a photograph, film, or video message or during a live appearance. The most common use of product placement is in films where characters use branded products.

Both product placement and sponsorship decisions are based on a shared target market. No matter the public relations vehicle, there must be a common buyer that all parties want to reach.

Examples of PR Campaigns

Since its modern inception in the early 20th century, PR has turned out countless campaigns—some highly successful, others dismal failures. Some of these campaigns have become particularly significant for their lasting influence or creative execution. This section describes a few notable PR campaigns over the years.

Diamonds For The Common Man

During the 1930s, the De Beers company had an enormous amount of diamonds and a relatively small market of luxury buyers. They launched a PR campaign to change the image of diamonds from a luxury good into an accessible and essential aspect of American life. The campaign began by giving diamonds to famous movie stars, using their built-in publicity networks to promote De Beers. The company created stories about celebrity proposals and gifts between lovers that stressed the size of the diamonds given. These stories were then given out to selected fashion magazines. The result of this campaign was the popularization of diamonds as one of the necessary aspects of a marriage proposal (Reid, 2006).

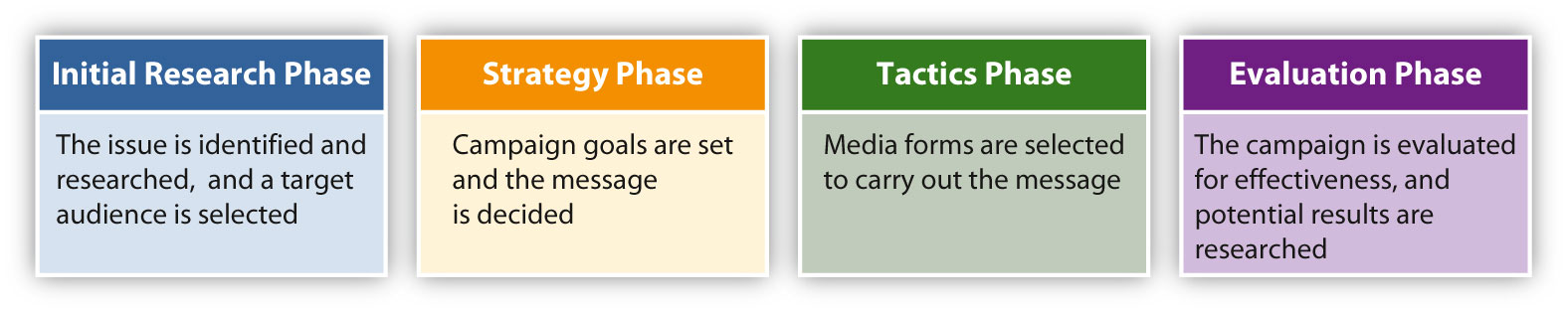

Big Tobacco Aids Researchers

In 1953, studies showing the detrimental health effects of smoking caused a drop in cigarette sales. An alliance of tobacco manufacturers hired the PR group Hill & Knowlton to develop a campaign to deal with this problem. The first step of the campaign Hill & Knowlton devised was the creation of the Tobacco Industry Research Committee (TIRC) to promote studies that questioned the health effects of tobacco use. The TIRC ran advertisements featuring the results of these studies, giving journalists who were addressing the subject an easy source to quote. The groups working against smoking were not familiar with media relations, making it harder for journalists to quote them and use their arguments.

The campaign was effective, however, not because it denied the harmful effects of smoking but because it stressed the disagreements between researchers. By providing the press with information favorable to the tobacco manufacturers and publicly promoting new filtered cigarettes, the campaign aimed to replace the idea that smoking was undeniably bad with the idea that there was disagreement over the effects of smoking. This strategy served tobacco companies well up through the 1980s.

PR as a Replacement For Advertising

In some cases, PR has begun overtaking advertising as the preferred way of promoting a particular company or product. For example, the tobacco industry offers a good case study of the migration from advertising to PR. Regulations prohibiting radio and TV cigarette advertisements had an enormous effect on sales. In response, the tobacco industry began using PR techniques to increase brand presence.

Tobacco company Philip Morris started underwriting cultural institutions and causes as diverse as the Joffrey Ballet, the Smithsonian, environmental awareness, and health concerns. Marlboro sponsored events that brought a great deal of media attention to the brand. For example, during the 1980s, the Marlboro Country Music Tour took famous country stars to major coliseums throughout the country and featured talent contests that brought local bands up on stage, increasing the audience even further. Favorable reviews of the shows generated positive press for Marlboro. Later interviews with country artists and books on country music history have also mentioned this tour.

From Advertising to PR Branding

While advertising is an essential aspect of initial brand creation, PR campaigns are vital to developing the more abstract aspects of a brand. These campaigns work to position a brand in the public arena in order to give it a sense of cultural importance. Pioneered by such companies as Procter & Gamble during the 1930s, the older, advertising-centric model of branding focused on the product, using advertisements to associate a particular branded good with quality or some other positive cultural value. Yet, as consumers became exposed to ever-increasing numbers of advertisements, traditional advertising’s effectiveness dwindled. The ubiquity of modern advertising means the public is skeptical of—or even ignores—claims advertisers make about their products. This credibility gap can be overcome, however, when PR professionals using good promotional strategies step in.

The new PR-oriented model of branding focuses on the overall image of the company rather than on the specific merits of the product. This branding model seeks to associate a company with specific personal and cultural values that hold meaning for consumers. Apple has employed this type of branding with great effectiveness. By focusing on a consistent design style in which every product reinforces the Apple experience, the computer company has managed to position itself as a mark of individuality. Despite the cynical outlook of many Americans regarding commercial claims, the notion that Apple is a symbol of individualism has been adopted with very little irony. Douglas Atkin, who has written about brands as a form of cult, readily admits and embraces his own brand loyalty to Apple:

I’m a self-confessed Apple loyalist. I go to a cafe around the corner to do some thinking and writing, away from the hurly-burly of the office, and everyone in that cafe has a Mac. We never mention the fact that we all have Macs. The other people in the cafe are writers and professors and in the media, and the feeling of cohesion and community in that cafe becomes very apparent if someone comes in with a PC. There’s almost an observable shiver of consternation in the cafe, and it must be discernable to the person with the PC, because they never come back.

Brand managers that once focused on the product now find themselves in the role of community leaders, responsible for the well-being of a cultural image (Atkin, 2004).

Kevin Roberts, the current CEO of Saatchi & Saatchi Worldwide, a branding-focused creative organization, has used the term “lovemark” as an alternative to trademark. This term encompasses brands that have created “loyalty beyond reason,” meaning that consumers feel loyal to a brand in much the same way they would toward friends or family members. Creating a sense of mystery around a brand generates an aura that bypasses the usual cynical take on commercial icons. A great deal of Apple’s success comes from the company’s mystique. Apple has successfully developed PR campaigns surrounding product releases that leak selected rumors to various press outlets but maintain secrecy over essential details, encouraging speculation by bloggers and mainstream journalists on the next product. All this combines to create a sense of mystery and an emotional anticipation for the product’s release.

Emotional connections are crucial to building a brand or lovemark. An early example of this kind of branding was Nike’s product endorsement deal with Michael Jordan during the 1990s. Jordan’s amazing, seemingly magical performances on the basketball court created his immense popularity, which was then further built up by a host of press outlets and fans who developed an emotional attachment to Jordan. As this connection spread throughout the country, Nike associated itself with Jordan and also with the emotional reaction he inspired in people. Essentially, the company inherited a PR machine that had been built around Jordan and that continued to function until his retirement (Roberts, 2003).

Branding Backlashes

An important part of maintaining a consistent brand is preserving the emotional attachment consumers have to that brand. Just as PR campaigns build brands, PR crises can damage them. For example, the massive Gulf of Mexico oil spill in 2010 became a PR nightmare for BP, an oil company that had been using PR to rebrand itself as an environmentally friendly energy company.

In 2000, BP began a campaign presenting itself as “Beyond Petroleum,” rather than British Petroleum, the company’s original name. By acquiring a major solar company, BP became the world leader in solar production and in 2005 announced it would invest $8 billion in alternative energy over the following 10 years. BP’s marketing firm developed a PR campaign that, at least on the surface, emulated the forward-looking two-way symmetric PR model. The campaign conducted interviews with consumers, giving them an opportunity to air their grievances and publicize energy policy issues. BP’s website featured a carbon footprint calculator consumers could use to calculate the size of their environmental impact (Solman, 2008). The single explosion on BP’s deep-water oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico essentially nullified the PR work of the previous 10 years, immediately putting BP at the bottom of the list of environmentally concerned companies.

A company’s control over what its brand symbolizes can also lead to branding issues. The Body Shop, a cosmetics company that gained popularity during the 1980s and early 1990s, used PR to build its image as a company that created natural products and took a stand on issues of corporate ethics. The company teamed up with Greenpeace and other environmental groups to promote green issues and increase its natural image.

By the mid-1990s, however, revelations about the unethical treatment of franchise owners called this image into serious question. The Body Shop had spent a great deal of time and money creating its progressive, spontaneous image. Stories of travels to exotic locations to research and develop cosmetics were completely fabricated, as was the company’s reputation for charitable contributions. Even the origins of the company had been made up as a PR tool: The idea, name, and even product list had been ripped off from a small California chain called the Body Shop that was later given a settlement to keep quiet. The PR campaign of the Body Shop made it one of the great success stories of the early 1990s, but the unfounded nature of its PR claims undermined its image dramatically. Competitor L’Oréal eventually bought the Body Shop for a fraction of its previous value (Entine, 2007).

Other branding backlashes have plagued companies such as Nike and Starbucks. By building their brands into global symbols, both companies also came to represent unfettered capitalist greed to those who opposed them. During the 1999 World Trade Organization protests in Seattle, activists targeted Starbucks and Nike stores with physical attacks such as window smashing. Labor activists have also condemned Nike over the company’s use of sweatshops to manufacture shoes. Eventually, Nike created a vice president for corporate responsibility to deal with sweatshop issues.

Relationship With Politics And Government

Politics and PR have gone hand in hand since the dawn of political activity. Politicians communicate with their constituents and make their message known using PR strategies. Benjamin Franklin’s trip as ambassador to France during the American Revolution stands as an early example of political PR that followed the publicity model. At the time of his trip, Franklin was an international celebrity, and the fashionable society of Paris celebrated his arrival; his choice of a symbolic American-style fur cap immediately inspired a new style of women’s wigs. Franklin also took a printing press with him to produce leaflets and publicity notices that circulated through Paris’s intellectual and fashionable circles. Such PR efforts eventually led to a treaty with France that helped the colonists win their freedom from Great Britain (Isaacson, 2003).

Famous 20th-century PR campaigns include President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Fireside Chats, a series of radio addresses that explained aspects of the New Deal. Roosevelt’s personal tone and his familiarity with the medium of radio helped the Fireside Chats become an important promotional tool for his administration and its programs. These chats aimed to justify many New Deal policies, and they helped the president bypass the press and speak directly to the people.

The proliferation of media outlets and the 24-hour news cycle have led to changes in the way politicians handle PR. The gap between old PR methods and new ones became evident in 2006, when then–Vice President Dick Cheney accidentally shot a friend during a hunting trip. Cheney, who had been criticized in the past for being secretive, did not make a statement about the accident for three days. Republican consultant Rich Galen explained Cheney’s silence as an older PR tactic that tries to keep the discussion out of the media. However, the old trick is less effective in the modern digital world.

That entire doctrine has come and gone. Now the doctrine is you respond instantaneously, and where possible with a strong counterattack. A lot of that is because of the Internet, and a lot of that is because of cable TV news (Associated Press, 2006).

Lobbyists also attempt to influence public policy using PR campaigns. The Water Environment Federation, a lobbying group representing the sewage industry, initiated a campaign to promote the application of sewage on farms during the early 1990s. The campaign came up with the word biosolids to replace the term sludge. Then it worked to encourage the use of this term as a way to popularize sewage as a fertilizer, providing information to public officials and representatives. In 1992, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency adopted the new term and changed the classification of biosolids to a fertilizer from a hazardous waste. This renaming helped New York City eliminate tons of sewage by shipping it to states that allowed biosolids (Stauber & Rampton, 1995).